This year, for the first time, I attended the Cheltenham Science Festival as a tourist. And it was great!! I was particularly pleased to see how much geoscience there was there, and had a number of great chats with scientists and engineers on the value of the festival and of the work or research that they were doing. As a quick snapshot, here are a few of my favourite things from the festival…

Tag Archives: science communication

Where is the line between academic criticism and personal attack?

As an academic, you expect criticism (and no, not from my parents about getting a ‘real job’, they are very supportive!). In a way, it’s kind of your job to both give and receive criticism of the research that you read, but recently I have been wondering about the line between criticism and personal attack. Whilst at the EGU Conference, I was shocked to attend a session where a member of the audience attacked a young researcher, calling her research ‘trivial’. This experience was surprising to me, because up until that point I had seen and been involved in many debates about different reserach, but never had one been addressed with such apparent vitriol. Now I didn’t know either of the researchers involved, so perhaps there was a personal relationship at work there, but nevertheless, it seemed really unprofessional – where was the constructive aspect that, if you thought the research was substandard, could move it forward and improve it? Isn’t that the point?

A possible reason for conflict could be in the difference between an experimental researcher and a computational reseracher, but the question I would ask then is, in that case does the one have any right to critically assess the other, without at least an attempt at understanding? And in that circumstance of an open debate, should you have another method of expressing your feedback if you are not an expert in that area? I say this with trepidation, because I personally am of the opinion that anyone should have the opportunity to comment on scientific research, whatever their background and area of expertise, and some of my best advice has come from researchers outside my field. Having said that, all of that advice was offered constructively and with good intentions.

But possible ‘attack’ rather than criticism doesn’t just occur between researchers from different fields. I recently saw another example of the blurred line between academic criticism and personal attack at a seminar I attended, where a young researcher was critiqued in increasingly aggressive and dismissive language by a more established member of the staff. This at least started out as genuine criticism, but when the researcher tried to defend their evidence in the face of an alternative interpretation, the staff member replied with increasing hostility. Now, in this case, although both academics were in the same field, one was older and more established, but the second academic was younger and had just won a prestigious grant, so perhaps there was a case of professional jealousy happening here. Still, I could only think of the other young researchers present, like myself, who were perhaps thinking – I don’t want to subject myself to this!

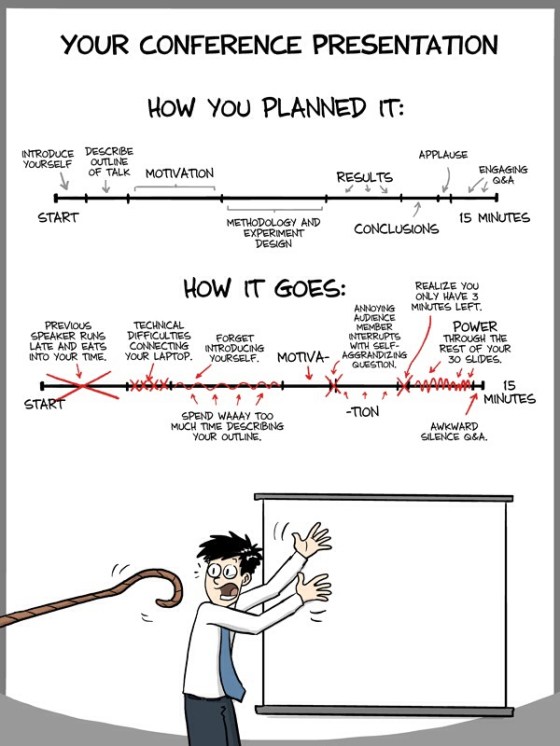

A PhD Comic about presenting at a conference that in many cases is scarily accurate…!

Now I have to make it clear here, I am in no way against the current method of presenting your results for criticism. Without an open and transparent way to examine each other’s data – how can we avoid scientific research from become corrupt? What I think needs to change is the way that those few researchers who respond aggressively are treated themselves in the scientific community. In the same way as misbehaviour is treated in the workplace, personal attacks should be banned in scientific conferences and seminars. Those who let their criticism slide into attack should be given a warning that they will not be allowed to comment again if this continues, and moderators should be very clear that this kind of behaviour is not tolerated. I will at this point say that in both circumstances I observed, the moderators were very good at defending the presenter in the firing line, but I still felt that there was a general acceptance of this behaviour, because it was seen as criticism. One of the hardest things to do as a scientist is to remove your personal feelings from your data as much as possible and this HAS to carry over to criticism as well.

A concerning flip side of this coin is the willingness of academics and researchers to present new and possibly controversial ideas. If you feel confident that it is only your data and results that will be questioned then you will be happy to submit your idea for criticism, as you would hope that concerns will either be answered or will reveal any weaknesses in your idea that you can address. However, if you feel that you yourself will become the subject of the criticism, most people – understandably – would not want to put themselves in that position and so would possibly not present their idea in the same way. It makes me think of all of those scientific discoveries that took decades to see the light of the scientific community because the authors were afraid of how they would be received. You only have to look at Charles Darwin to see how fear can control scientific data.

It’s a tricky topic – criticism is vital to keep scientists moving forward (and honest!), but when criticism becomes attack it can stifle scientific creativity. How do we balance the two? I feel like I should finish with a line from a show that really introduced the idea of combining constructive criticism and personal attack – The Jerry Springer Show:

“Until next time, take care of yourself – and each other.”

EGU 2014 – the conference of champions!

Well it’s that time of year – the time where if you email an academic, chances are you will get an out of office response. It’s not business time – those aren’t business socks, they are conference socks! It’s conference … Continue reading

Voice of the Future 2014

Last week on Wednesday the 19th March, I got the chance to attend an event called ‘Voice of the Future’ that allows early-career researchers and students to ask questions about science policy directly to the politicians who make the decisions. This event happens every year as a part of National Science and Engineering Week and draws student representatives of some of the largest scientific societies in Britain. I was asked to be a representative for the Geological Society, and I couldn’t have been more excited! Especially as it seems like so much happens behind closed doors that the ‘air of mystery’ is more of a fog…!

All those who attended had the opportunity to ask a question of the ‘witnesses’ (who would normally have been scientists, economists, etc; but this time were the politicians) and although there were far too many questions submitted than could possibly be asked, most of us at least got a chance to sit at the round table, just like in a real select committee meeting. One of the funny things was that you could be assigned a question asked by someone else, which was a little confusing, especially as you then didn’t necessarily know the background to the question. The questions ranged from public perceptions of scientists, to government funding, to evidence based policy making, and were split into four sessions, each with different witnesses.

The meeting was chaired by Victoria Charlton, from the Select Committee for Science and Technology and the meeting was opened by the Speaker of the House of Commons: John Bercow. Mr Bercow started the meeting by welcoming all the participants, but saying that he had had no interest in science at school – that it frightened him. I’m always saddened when I hear of a subject frightening a person – when knowledge and curiosity are something that is scary; I feel that’s when something has gone really wrong in that person’s educational experience. However, he moved on to say that he now thinks science is an important part of a rounded education (which is true!). He also moved on to describe the two types of politician according to the late Tony Benn; signposts (who have a fixed opinion and never change it) and weathercocks (who have no opinion at all). I was a bit concerned that these were described as the only types of politician as I would much rather have a politician with an opinion, but who was willing to change it in the face of good evidence, but maybe that’s just me!

We were then introduced to the first session of the day, with our witness Sir Mark Walport, the current Government Chief Scientific Advisor. Sir Mark answered questions on medical technology, Care.data, gender equality in science, the UK’s role in the international scientific community, evidence based policy and how to become Chief Science Advisor. The first question he was asked was about how to tackle the current negative perception of science and scientists, which he answered with my favourite quote of the day:

“You talk about the public understanding of science, but it’s equally important that scientists understand the public as well and so I think we are in a world where we need a public engagement actually – it’s about a two way conversation between the scientific community and all the publics.”

He then proceeded to refer to the recently published Public Attitudes to Science (PAS) survey which highlighted that actually the public don’t seem to perceive science and scientists negatively at all – quite the opposite in fact! This kind of question was repeated in the second session as well, which led me to think firstly that maybe scientists have a defensive view of how we are perceived by the public and also possibly that not many of the question askers were aware of the PAS study (either the most recent one, or any of its previous versions) as this seemed an unusual point to be labouring.

Another question Sir Mark was asked was:

“Do you think the media is dangerously irresponsible in the way that it reports on scientific topics?”

His answer to this was really interesting in my opinion, as he said that perhaps it wasn’t that the media was dangerously irresponsible, but more ‘dangerously variable’. That we can’t think of the media as a single element, and that some reporters work hard and are very effective. He also noted that it ‘takes two to tango’ that scientists must not ‘over claim’ and beware of their data being sensationalised.

The second session was with members of the Science and Technology Committee; Andrew Miller, Pamela Nash, David Tredinnick, David Heath, Stephen Metcalfe, Sarah Newton and Jim Dowd. This was very interesting as the panel format gave rise to more of a debate between witnesses and also created my second favourite quote of the day. In response to the question:

“How important is it that the general public understand the true value of the medicines that they take and have the opportunity to have a say on this?”

David Tredinnick brought up the subject of homeopathic medicine in response to this question, but I couldn’t help but think that this was TOTALLY the wrong crowd for that. I mean you are speaking to a room full of early careers researchers, who in many cases have had to fight and claw for the little funding they have managed to secure and they are researchers representing the Society of Biology, the Biochemical Society, the Society for Applied Microbiology, the British Pharmacological Society, the Society for Endocrinology, the Campaign for Science and Engineering – and the rest who may not have been medical researchers, but still tend toward the skeptical end of the spectrum!! Still David Heath stepped in with the brilliant reply:

“I feel like I’m being drawn into an argument I don’t want to have, I just prefer evidence rather than… magic.”

You could tell that his response went down well in the room! Other questions asked in this session related to the Haldane principle, the science curriculum, nuclear reactors, access to scientific information, what researchers can do to become more engaged with Parliament, GM crops and evidence based policy. The panel were also asked:

“What single major scientific discovery would you hope to see in your lifetime?”

The answers were varied and interesting, from room temperature superconductivity, issues around resistance to antibiotics and deep space exploration. David Tredinnick suggested electricity transmitted ‘through the ether’, and whilst David Heath initially plugged for supermarket packaging that you could actually open, he actually wanted to see medical tri-corders invented (extra points for the Star Trek reference). Stephen Metcalfe wanted a better understanding of the origins of disease and Andrew Miller finished with a big picture wish – to better learn how to manage the limited resources of our planet.

The witness for the third panel was Liam Byrne, the Shadow Minister for Business, Innovation and Skills. He answered questions on life science investment, evidence based policy, Scotland’s potential independence, MP’s access to scientific advice and retention of young scientists and engineers. He also answered the question:

“If the Government’s ambition to obtain highly skilled professionals from all backgrounds was real, would the first step not be to extend student loan funding to Masters level students, enabling a greater number of students to undertake professional postgraduate study?”

Mr Byrnes answer was yes, as he understood now that in some fields in order to distinguish yourself you need to have postgraduate study, and that we cannot leave our workforce’s career development in the hands of the large banking corporations.

The fourth session was attended by David Willetts, the Minister for Universities and Science – who was late. When he did arrive, he was quite short with his answers (and I understand that it was Budget Day, but a) I think that applied to everyone else as well and b) if he was too busy he should have just said no), but answered on the topics of science teachers, the focus of funding research, the privatisation of NERC research centres, encouraging diversity, development of space technology, immigration and the skilled researcher brain drain.

The meeting was concluded by Andrew Miller saying that whilst the meeting was a good start, it was incumbent upon us to keep in contact – tell our MP’s about our research, send in evidence for consideration and to keep talking about policy that we value.

“We need your help” he said, and of course, he is right.

So I know this was a long post, but I think it was worth it. The photographs were used by kind permission of the Society of Biology (contact Dr Rebecca Nesbit) and if you want to see the meeting, the video of the session is avalible here.

Am I a science evangelist?

Recently I have been hearing a lot of references to science evangelism, mostly indicating someone who is really really passionate about communicating science. Now the second part (especially when it comes to geology) is definitely true about me, but I’m slightly unsure about the ‘evangelising’ part. I grew up in South Devon, not really a part of the world known for extremely strong religious beliefs, but there were a number of devout religious practitioners in my street and the nearby community. I knew the kids from some of these families, we went to school together and played together, but every so often they would come to our house, all dressed up smartly, to try and sell us their religion. Now realistically I imagine the children that I was friends with probably didn’t care if we wanted to be the same religion as them so long as we were willing to go off on adventures through the woods and play on the swings, but their parents did care. I remember how excruciatingly uncomfortable these little visits would be – my parents aren’t particularly religious, but when the person with a pamphlet lives a few houses away and their kids play with yours, it’s a lot harder to turn them away!

I think this is where my problem with ‘evangelism’ comes from. An evangelist is defined in the Oxford dictionary as:

EVANGELIST (noun)

- A person who seeks to convert others to the Christian faith, especially by public preaching

- A layperson engaged in Christian missionary work

- A zealous advocate of a particular cause

- The writer of one of the four Gospels (Matthew, Mark, Luke, or John)

Now I do love science, and do I think people would be better off if they understood more science (and geology)? Absolutely. But I don’t need people to believe in science – to want to make it their life’s work or suddenly go start chemistry busking in Croydon (although either of these things would be awesome). Now just to clarify, I still think everyone can do science (and should understand the basics), I just don’t think it needs to be number 1 priority for everyone.

I like having friends who are lawyers, accountants and historians, who sing with beauty and fire or can name pretty much every rugby player that England has had for the last decade (yes Jen, I’m looking at you). Science is great, it challenges you and forces you to look at the world through new eyes. But it is not the only beautiful and challenging thing about our lives. The question I have to ask is in that case do we need to redefine what evangelism means in a science communications sense? I think we do.

So I have decided to redefine science evangelism for myself.

SCIENCE EVANGELIST (noun)

- A person who shares their enjoyment of science and curiosity about the world; without judgement, superiority or sometimes even company!

If a scientist evangelises in forest when no-one is there, do they actually make a sound?!?