This year, for the first time, I attended the Cheltenham Science Festival as a tourist. And it was great!! I was particularly pleased to see how much geoscience there was there, and had a number of great chats with scientists and engineers on the value of the festival and of the work or research that they were doing. As a quick snapshot, here are a few of my favourite things from the festival…

Category Archives: Science Communication

Where is the line between academic criticism and personal attack?

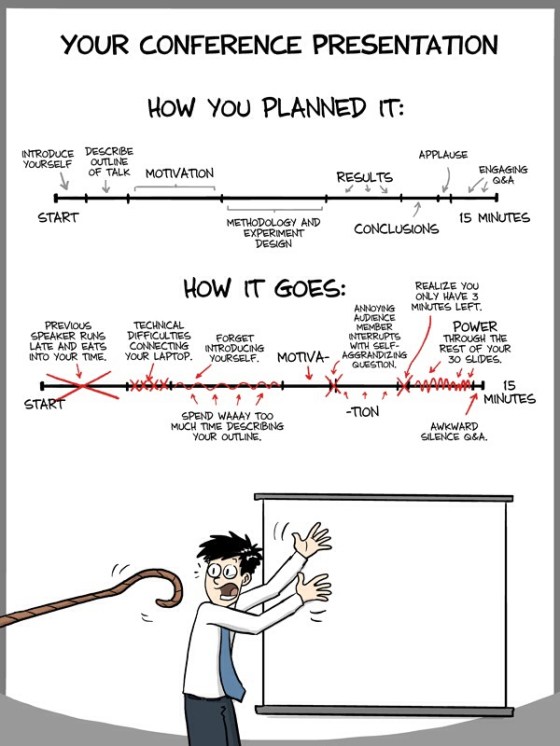

As an academic, you expect criticism (and no, not from my parents about getting a ‘real job’, they are very supportive!). In a way, it’s kind of your job to both give and receive criticism of the research that you read, but recently I have been wondering about the line between criticism and personal attack. Whilst at the EGU Conference, I was shocked to attend a session where a member of the audience attacked a young researcher, calling her research ‘trivial’. This experience was surprising to me, because up until that point I had seen and been involved in many debates about different reserach, but never had one been addressed with such apparent vitriol. Now I didn’t know either of the researchers involved, so perhaps there was a personal relationship at work there, but nevertheless, it seemed really unprofessional – where was the constructive aspect that, if you thought the research was substandard, could move it forward and improve it? Isn’t that the point?

A possible reason for conflict could be in the difference between an experimental researcher and a computational reseracher, but the question I would ask then is, in that case does the one have any right to critically assess the other, without at least an attempt at understanding? And in that circumstance of an open debate, should you have another method of expressing your feedback if you are not an expert in that area? I say this with trepidation, because I personally am of the opinion that anyone should have the opportunity to comment on scientific research, whatever their background and area of expertise, and some of my best advice has come from researchers outside my field. Having said that, all of that advice was offered constructively and with good intentions.

But possible ‘attack’ rather than criticism doesn’t just occur between researchers from different fields. I recently saw another example of the blurred line between academic criticism and personal attack at a seminar I attended, where a young researcher was critiqued in increasingly aggressive and dismissive language by a more established member of the staff. This at least started out as genuine criticism, but when the researcher tried to defend their evidence in the face of an alternative interpretation, the staff member replied with increasing hostility. Now, in this case, although both academics were in the same field, one was older and more established, but the second academic was younger and had just won a prestigious grant, so perhaps there was a case of professional jealousy happening here. Still, I could only think of the other young researchers present, like myself, who were perhaps thinking – I don’t want to subject myself to this!

A PhD Comic about presenting at a conference that in many cases is scarily accurate…!

Now I have to make it clear here, I am in no way against the current method of presenting your results for criticism. Without an open and transparent way to examine each other’s data – how can we avoid scientific research from become corrupt? What I think needs to change is the way that those few researchers who respond aggressively are treated themselves in the scientific community. In the same way as misbehaviour is treated in the workplace, personal attacks should be banned in scientific conferences and seminars. Those who let their criticism slide into attack should be given a warning that they will not be allowed to comment again if this continues, and moderators should be very clear that this kind of behaviour is not tolerated. I will at this point say that in both circumstances I observed, the moderators were very good at defending the presenter in the firing line, but I still felt that there was a general acceptance of this behaviour, because it was seen as criticism. One of the hardest things to do as a scientist is to remove your personal feelings from your data as much as possible and this HAS to carry over to criticism as well.

A concerning flip side of this coin is the willingness of academics and researchers to present new and possibly controversial ideas. If you feel confident that it is only your data and results that will be questioned then you will be happy to submit your idea for criticism, as you would hope that concerns will either be answered or will reveal any weaknesses in your idea that you can address. However, if you feel that you yourself will become the subject of the criticism, most people – understandably – would not want to put themselves in that position and so would possibly not present their idea in the same way. It makes me think of all of those scientific discoveries that took decades to see the light of the scientific community because the authors were afraid of how they would be received. You only have to look at Charles Darwin to see how fear can control scientific data.

It’s a tricky topic – criticism is vital to keep scientists moving forward (and honest!), but when criticism becomes attack it can stifle scientific creativity. How do we balance the two? I feel like I should finish with a line from a show that really introduced the idea of combining constructive criticism and personal attack – The Jerry Springer Show:

“Until next time, take care of yourself – and each other.”

5 things you wouldn’t expect to find at a geology conference

One of the things that I realised whilst at EGU last week was how broad the subject of geology actually is and how we don’t always appreciate the breadth of our subject. Some of this obviously come from the influence of interdisciplinary studies like my own, but some it comes from the unique and innovative ways that geoscientists are attempting to broaden our understanding of the planet. To highlight this I have picked out 5 things you wouldn’t expect to see at a geology conference – some more than others.

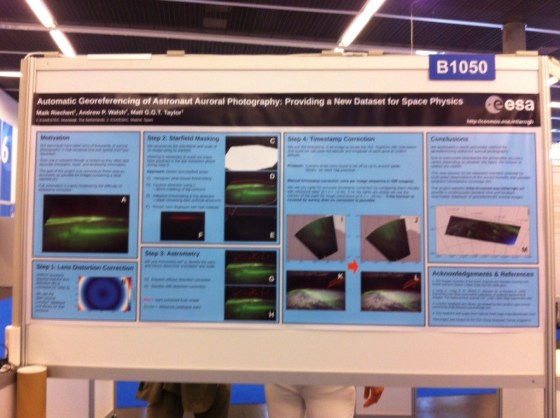

1- Astronaut photographs

‘Automatic Georeferencing of Astronaut Auroral Photography: Providing a New Dataset for Space Physics‘ from Multi-scale Plasma Processes in the Earth’s Environment session (ST2.2) – using data from recent space missions to advance our understanding of space physics.

Recently, the work of astronaut Commander Hadfield brought the activities of the people who get strapped to a rocket and propelled beyond our atmosphere to learn more about our planet back into the public eye. But although the images they produce are beautiful, inspiring and humbling all at the same time, they are often not very useful because there is no way for scientists to tell the scale of the image or where exactly it was taken. The work of Reichart, Walsh and Taylor addresses this problem by using ‘starfield recognition software‘ to calculate the height and location of the images. Now I don’t know about you, but there is something so romantic sounding about starfield recognition software. It makes me think that the software we so often associate with catching criminals can actually be used for something uplifting and will, once fully developed, improve our understanding of how the Auroras (both Australis and Borealis) work.

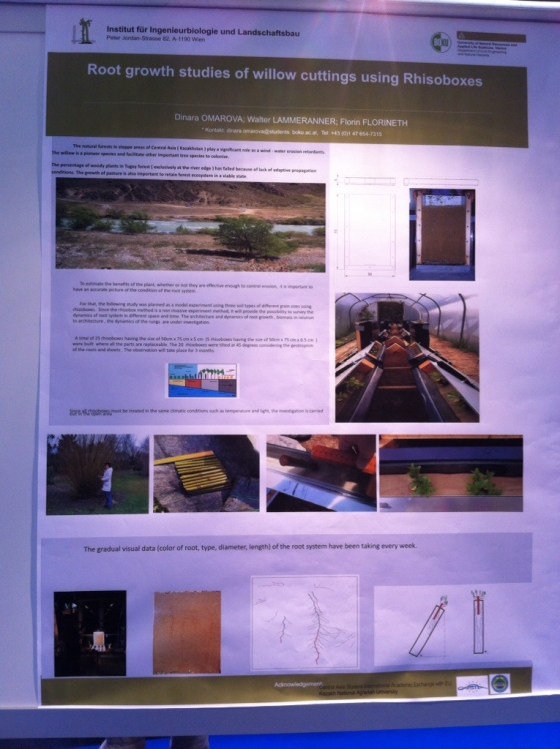

2- Willow tree root growth patterns

‘Root Growth Studies of Willow Cuttings using Rhisoboxes‘ from How Vegetation Influences Soil Erosion and Slope Stability: Monitoring and Modelling Eco-hydrological and Geo-mechanical Factors session (SSS2.10/BG9.7/GM4.8/HS8.3.9/NH3.9) – the relationship between vegetation and how soil behaves, especially focussing on land restoration projects and management plans.

When you think of geology, willow is probably not the first thing that springs to mind. However, when you think about landslides – which are most definitely geological – the presence, absence or behaviour of plants is very important. In Central Asia (amongst other places) willow is vital in facilitating the colonisation of other tree species in forests that help protect the soil from erosion. This study, although it seems like it belongs in a botany (or at least biology) conference is actually examining the material necessary to mitigate the effects of erosion, which can lead to lots of other geological problems.

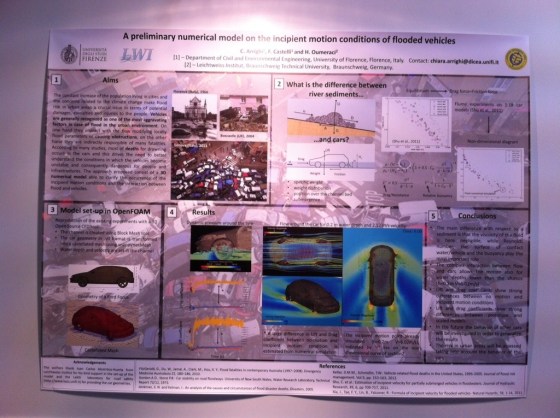

3- Fluid dynamics of cars

‘A Preliminary Numerical Model on the Incipient Motion Conditions of Flooded Vehicles‘ from Flood Risk and Uncertainty session (NH1.6) – predicting current and future flood risk using state of the art flood risk assessment methodologies.

This had to be one of my favourite posters – mostly due to the obvious/unexpected dichotomy of the contents. If you picture a flood, what do you see? Rushing muddy brown water tearing away at the countryside, carrying the odd tree? Perhaps. But more and more often nowadays floods are affecting our urban areas, and the thing the floodwater is likely to be dragging is a car not a tree. This work by Arrighi, Castelli and Oumeraci takes a closer look at how vehicles are affected by flood water and how they affect the flow themselves. It’s also a sobering look at how easy it is to loose control of a vehicle in a flood and explains why most studies identify the greatest cause of deaths from drowning in a flood to be a car.

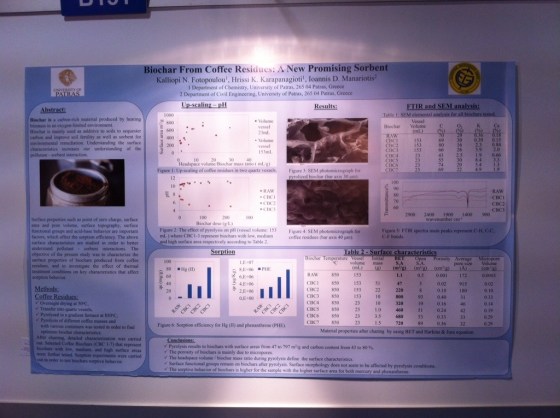

4- Coffee residue

‘Biochar from Coffee Residues: A New Promising Sorbent‘ from Novel Sorbent Materials for Environmental Remediation session (SSS9.8) – the use of sorbent materials (a material that can collect molecules of another substance) for environmental applications.

If the conference last week was attended by over 12,000 delegates, how many cups of coffee were drunk do you think (added to the fact that it was nigh on impossible to get a good cup of tea)? Now imagine you could take the dregs of all that coffee and do something useful with it! Well that is precisely what Fotopoulou, Karapanagioti and Manariotis were exploring- how to use coffee residues to make biochar. Biochar is a carbon-rich substance that is added to soils in order to sequester carbon, improve the quality (fertility) of the soil and assist in environmental remediation. Who knew an old cup of coffee could be so useful?!

5- Wind patterns in the Pacific

‘Origin of Wind Events in the Equatorial Pacific‘ from ENSO: Dynamics, Predictability and Modelling session (NP2.1) – ENSO stands for the El Niño Southern Oscillation and includes all studies of El Niño and La Niña.

So wind may not be that disconnected from geology – but wind patterns? Over water? Yes at a geology conference a geoscientist’s awareness of the processes that shape our planet extends even to the climate. Which is not all that surprising really when you consider that one of the biggest issues and areas of study that geologists deal with nowadays is climate change.

These are only the posters that I came across and thought interesting during the conference – I’m sure there were many many more! Did you see any examples of a poster or a presentation that you wouldn’t expect to see at a geology conference?!

EGU 2014 Day 5 – The big presentation, widening participation and communicating global risk

So here we are. The final day at EGU and I’m about to present in my first international conference. To add to all that I actually have a pretty busy day as I have to be in Lyme Regis in Dorset this evening – so packing, catching the flight and driving for 3 hours back to Lyme were all also in my schedule today. Nevertheless I appeared all ready for my talk at 8am this morning – and was welcomed by my name on the board!

The session I was presenting in was called ‘Geoscience Education for Sustainable Development and Widening Participation‘ (EOS7) and was a mix of talks looking at geoscience communication and understanding from how to communicate your science, to using serious games to increase understanding about CO2 storage, to using place-based learning to help students engage with geology. Now I know I’m biased, but I thought the session was great – lots of interesting ideas and new concepts. My talk went pretty well I think – I always worry about speaking to an academic audience, especially when I’m an interdisciplinary. How many terms from cognitive science can I use without it being jargon? This is a highly educated audience after all! So I retreated into my preferred method of assuming some knowledge, but embroidering any terms with an accompanying image or explanation. I hope it worked!! In any case, after the initial terror faded I actually really enjoyed it (despite having to present after the dynamic and accessible presenting style of Sam Illingworth – gulp!). Hooray!

The orals were followed by the poster session of the same name, and I went along to have a look at the posters presented. Again there was a huge variety, but one of my favourites was about ‘A New Protocol in La Spezia for Elementary and Secondary School Students for Monitoring Perception Towards Science and Performance in School Classrooms‘. I had a long talk with Mascha Stroobant and Silvia Merlino about their research and during this talk I couldn’t help thinking how it was really difficult to know what was happening in science perception studies in other countries as all our research is at such an early stage. There seemed to be no advanced or established research in science perception at EGU (that I could find, but I will kick myself if there was and I missed it), which makes it difficult to know what mistakes have been made before, how to avoid those pitfalls and the best methods for ensuring we have valid data.

My final session of Friday (and of EGU) was ‘Global and Continental Scale Risk Assessment for Natural Hazards: Methods and Practice‘ (NH9.13). I could only go to half of this session and I wanted to go to support a friend who was presenting there – the brilliant Joel Gill, PhD student at Kings College London and founder/director of Geology for Global Development. He was presenting his work on ‘Reviewing and Visualising Relationships Between Anthropic Processes and Natural Hazards within a Multi-Hazard Framework‘. The brilliant thing about his research is that he presents risk within a continuum of natural and anthropic causes of hazard, not just in terms of vulnerability.

Unfortunately after Joel’s talk I had to dash off to catch the coach and so that was the end of my first EGU experience. I learned that geoscience is a much broader subject than I ever thought it was, and that people like myself in all varieties of interdisciplinary research are attempting to expand our understanding of the planet to new fronteirs. I learned that communication and public understanding of geology isn’t just important to industry, but to ALL geoscientists and even those working in narrow fields see the value of speaking about their research. I learned that I am part of a vibrant, enthusiastic and welcoming community, and all those things that I think I am alone in worrying about (because they are about interviews, psychology and data representation) are shared in different forms by many other reseracheres. I also learned that there is so much more to learn – and EGU just got me even more fired up to go back into the field and get back into my office – BRING ON THE DATA!!

EGU 2014 Day 4 – Global catastrophes, uncertainty and can you ever know your audience?

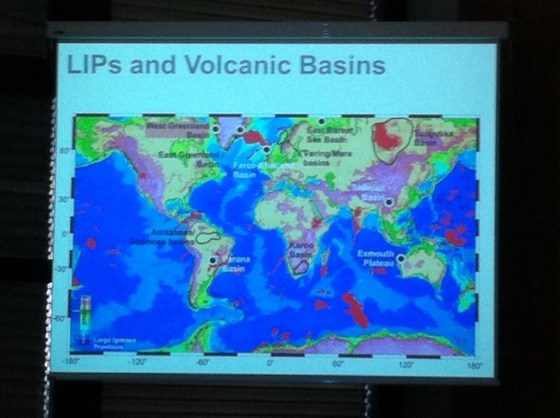

Day four in the big geology house…. Today started well, I took a little time in the morning to work on my presentation for tomorrow, but because I forgot to reset the clock on my computer I missed the workshop on applying for funding that I was aiming to attend. Nevertheless I made it to my first session of the day ‘Volcanism, Impacts, Mass Extinctions and Global Environmental Change‘ (SSP1.2/GMPV41) which is a session that has to win the prize for BEST NAME OF A SESSION EVER. I bumped into a lecturer from my University there, who seemed a little surprised to see me – he asked why I was there and I said ‘Global catastrophes? Of course I’m coming to this one!’ and he replied that he was there for the isotopes. Strangely the organisers seemed to underestimate the interest factor of such an epic session title, and had put the session in a really small room. People were crammed in all over the place, sat on the floor, standing by the walls, and every seat was full. You just can’t deny the pulling power of massive disasters.

The talks themselves were great, a series of presentations on Tunguska and the Siberian trap flood basalts and their associated infrastructure. There were questions of whether magamatism could trigger a mass extinction, and if the dates of massive flood basalt eruptions did actually precede the extinctions? Seth Burgess did actually present data that suggested the main body of the eruptions did actually commence AFTER the extinction, but also recognised the problem of sampling bias – a common problem in the geological sciences – that you can’t always get the data you want because, oh, a mountain is on top of it. So you have to predict as best you can based on incomplete data. From the data that Seth Burgess had, he suggested that there was more than one phase of the eruption and that the lavas that couldn’t be sampled may actually contain sills that predate the extinction.

Later on the session, the extinction moved from the end-Permian to the Cretaceous. Now if you are unfamiliar with that name – think dinosaurs. It’s the one where the famous film should really have been called Cretaceous Park instead (and why it wasn’t I really don’t know!). The thing with the end-Cretaceous extinction was that it happened not only at the same time as a massive flood basalt, but at the same time as a massive (and famous) meteorite impact called Chixulub. Mark Richards from the University of California, Berkeley, told us that there was a 1 in 5 chance of all of these events being a coincidence, which isn’t really that bad. But when you include the size of the Deccan eruptions, the chance becomes 1 in 50, so it is hard to dismiss this as a coincidence. He suggested that another reason for the correlation, was that the impact could have triggered massive worldwide magmatic activity – in the same way that seismic triggers have been shown to induce magmatic activity on a much smaller scale. A question was asked however, if there was any evidenced for this systemic increased activity and although at the moment there is not, Professor Richards thinks that geochemical data could be available to support this hypothesis.

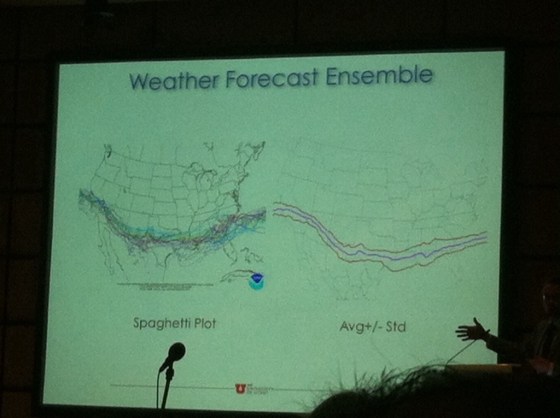

So from volcanoes and massive meteorite impacts I thought I would move on to uncertainty and the ‘Communication of Uncertainty about Information in Earth Sciences‘ (SSS11.1/ESSI3.6), convened by R Murray Lark from the BGS. This session was all about how we, as geoscientists, represent unceratinty. This is a really big deal, especially when you relate it to what I was saying above about sampling bias – a large amount of geological information is interpreted on, what the researchers would see as, less than perfect data sets. Now a lot of uncertainty work is based on how to represent a statistical analysis of the uncertainty to other geologists, but there is a growing interest in how we represent uncertainty to the public. Robert Kirby talked about how using ensemble data (think hurricane tracks) can help people to understand different types of data simultaneously, but by using means and standard deviation statistical analysis you can extract more meaningful data (which may be harder to understand). What was interesting to me, was the suggestion that non-experts would have a better understanding of the value of ensemble data that statistically analysed data, but this hadn’t been tested yet. In fact a lot of the work on public understanding of uncertainty seemed to be based upon assumptions – so perhaps these were initial results of studies that were ongoing.

The day ended with the Townhall meeting ‘You don’t know your audience! A ClimateSnack debate‘ (TM8). This meeting drew together a number of science communications experts from a variety of backgrounds to discuss ‘knowing your audience’ a central concept in sci comm and one that is often under debate. The panel consisted of:

Dr Sam Illingworth, a lecturer in Science Communication at Manchester Metropolitan University (read more about him here)

Christina Reed, an independant science journalist

Liz Kalaugher, from environmentalresearchweb

Prof David Shultz, a lecturer in Synoptic Meteorology at Manchester University and the author of Eloquent Science

Mathew Reeve, co-founder of ClimateSnack (the moderator)

The discussion covered a wide range of subjects relating to audience – can you ever know your audience, how do you know what your audience wants, where is ‘the room’ in a digital age? We even discussed the seemingly opposing views of should we even be attempting to communicate all forms of science (as some parts are genuinely too difficult to understand without four years of university education) and do we seek to maintain the ‘aura of mystery’ to preserve our academic importance? What was interesting here was the idea that as science communicators we all WANT to communicate every aspect of our science, but that is just unrealistic – and most people genuinely wouldnt care. What we have to do is make our science AVAILABLE instead.

Finally I asked about training our undergraduates in science communication and Prof Schultz raised an interesting point – that our undergraduates often have a hard enough time writing scientifically first and that writing for a general audience from a scientific perspective – especially as a scientists – often means you need to understand scientific writing before you can communicate it back to the public. Also, he said, in his experience students already think they can communicate with non-scientists without training!

This session finished at 8, so I trundled myself back to the hostel to prepare for my oral presentation tomorrow at 9.15am (eek!).